Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction: The Core Question

The Indian Constitution guarantees Fundamental Rights (Part III) — the foundation of liberty, equality, and justice.

Since independence, one recurring debate has shaped India’s constitutional history:

Can Parliament amend or alter Fundamental Rights?

This conflict between Parliament’s power to amend (Article 368) and Judiciary’s power to review (Article 13) defines the Constitutional balance of India.

The Constitutional Framework

Article 13

Prohibits the State from making laws violating Fundamental Rights.

Any such law is void.

Article 368

Grants Parliament the power to amend the Constitution “by way of addition, variation or repeal.”

Requires special majority (2/3 of members present + majority of total strength).

In some cases, ratification by half of the states is required.

Core Conflict:

Does “law” in Article 13 include constitutional amendments under Article 368?

This question became the root of the Parliament–Judiciary conflict.

Early Phase: Judicial Acceptance of Parliamentary Supremacy

(a) Shankari Prasad v. Union of India (1951)

Issue: Validity of the First Amendment Act, 1951, which curtailed the Right to Property (Article 31).

Judgment: Supreme Court upheld Parliament’s power to amend Fundamental Rights.

Held that “law” in Article 13 does not include constitutional amendments.

Impact: Parliament’s amending power = Unlimited at this stage.

(b) Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1965)

Issue: Validity of the 17th Amendment Act, 1964, protecting land reform laws from judicial review.

Judgment: Reaffirmed Shankari Prasad.

Observation: Justice Mudholkar hinted that Parliament’s power might be limited by the “basic features” of the Constitution.

This observation later evolved into the Basic Structure Doctrine.

Turning Point: Judicial Assertion

(a) I.C. Golaknath v. State of Punjab (1967)

Issue: Could Parliament amend Fundamental Rights (like right to property, equality, etc.)?

Judgment (6:5 Majority):

Parliament cannot amend Fundamental Rights.

Constitutional amendments = “law” under Article 13(2).

Hence, any amendment violating Fundamental Rights is void.

Result: Parliament temporarily lost the power to alter Fundamental Rights.

Impact: Created constitutional deadlock; prompted Parliament to respond through amendments.

Parliament’s Countermove: Constitutional Amendments

(a) 24th Amendment Act, 1971

Enacted to overrule Golaknath.

Key Provisions:

Explicitly declared that Parliament has power to amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights.

Clarified that a Constitutional Amendment is not “law” under Article 13.

Purpose: Restore Parliament’s supremacy in amending power.

(b) 25th Amendment Act, 1971

Gave primacy to Directive Principles (Part IV) over Fundamental Rights in case of conflict.

Introduced Article 31C — laws implementing certain Directive Principles cannot be challenged for violating Articles 14, 19, or 31.

Historic Showdown: Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973)

Background

A 13-judge bench — the largest ever — examined the validity of the 24th, 25th, and 29th Amendments.

Question: Is Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution unlimited?

Judgment (7:6 Majority):

Parliament can amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights.

BUT — it cannot destroy or alter the “Basic Structure” of the Constitution.

Key Elements of the Basic Structure Doctrine:

Supremacy of the Constitution

Rule of Law

Separation of Powers

Judicial Review

Federalism

Secularism

Democracy

Balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles

Impact:

Limited Parliament’s power — it can amend, but not abrogate essential constitutional features.

Restored balance between Parliamentary sovereignty and Judicial review.

Emergency Era and Parliament’s Overreach

(a) 42nd Amendment Act, 1976

Known as the “Mini-Constitution” passed during the Emergency (1975–77).

Attempted to curb judicial power and enhance Parliament’s supremacy.

Key Provisions:

Declared that no constitutional amendment could be questioned in court.

Gave Directive Principles precedence over Fundamental Rights.

Strengthened Executive control.

Effect:

Parliament attempted to make its amending power absolute, nullifying the Kesavananda Bharati limitation.

Judiciary’s Retaliation: Restoring Balance

(a) Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980)

Issue: Validity of 42nd Amendment provisions limiting judicial review.

Judgment:

Struck down clauses that gave unlimited power to Parliament.

Declared that “limited amending power is part of the Basic Structure.”

Reaffirmed that Judicial Review and Balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles form part of the Basic Structure.

Impact:

Restored the supremacy of the Constitution.

Reasserted that Parliament’s power is derived, not absolute.

Later Developments: Ninth Schedule and Judicial Review

(a) Waman Rao v. Union of India (1981)

Issue: Laws placed in the Ninth Schedule (protected from judicial review).

Judgment:

All laws inserted into the Ninth Schedule before April 24, 1973 (Kesavananda date) are valid.

But laws added after that date can be reviewed if they violate the Basic Structure.

(b) I.R. Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu (2007)

Judgment: Reaffirmed Waman Rao.

Any law, even if protected under the Ninth Schedule, is subject to Judicial Review if it violates the Basic Structure.

Conclusion from both cases:

→ The Basic Structure Doctrine stands supreme.

→ Parliament cannot place any law beyond judicial scrutiny.

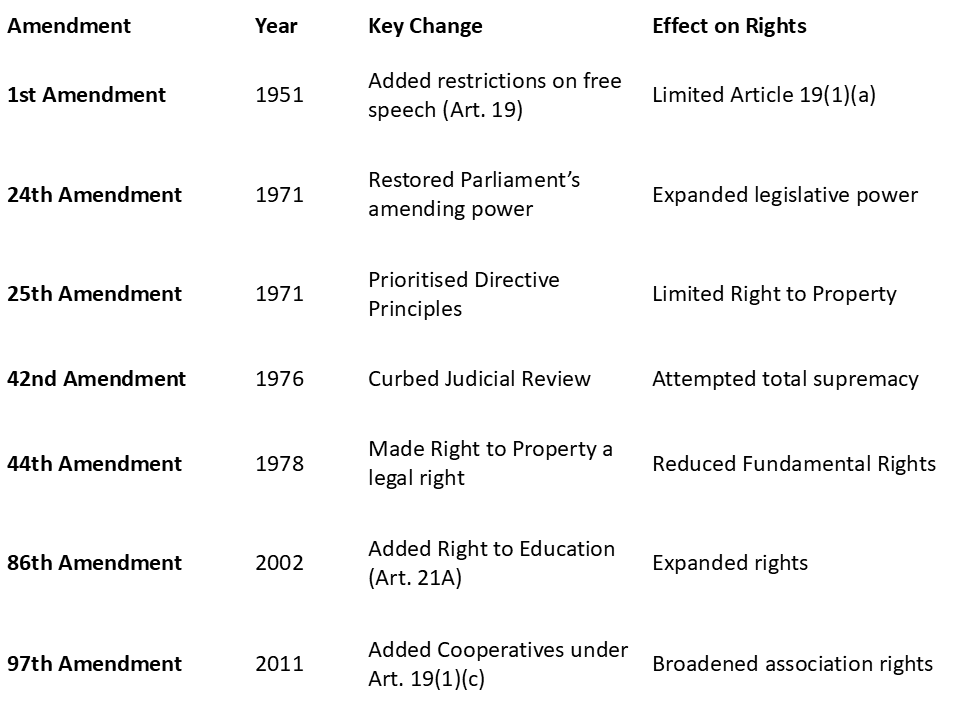

Major Amendments Affecting Fundamental Rights

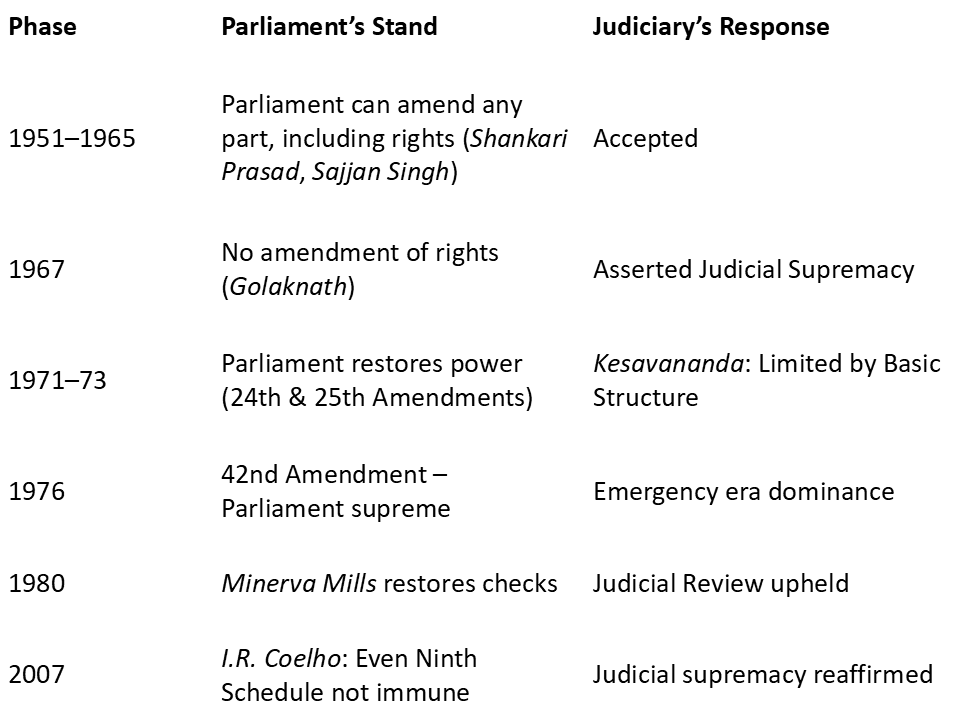

Parliament vs. Judiciary: A Summary of the Power Struggle

The Basic Structure Doctrine – India’s Constitutional Firewall

Essence:

-

Parliament can amend the Constitution to reflect changing needs,

but cannot destroy its essential features.

Core Elements (as evolved through judgments):

-

Supremacy of the Constitution

-

Rule of Law

-

Independence of Judiciary

-

Federalism

-

Democracy and Free Elections

-

Separation of Powers

-

Judicial Review

-

Secularism

-

Harmony between Fundamental Rights & Directive Principles

Purpose: To prevent any branch (especially Parliament) from turning democracy into dictatorship.

What Parliament Can and Cannot Do

Can Do:

Can Do:

-

Amend any provision of the Constitution.

-

Modify Fundamental Rights to suit social or economic goals.

-

Introduce new rights (e.g., Right to Education).

-

Impose reasonable restrictions (e.g., public order, morality).

Cannot Do:

Cannot Do:

-

Destroy the Constitution’s Basic Structure.

-

Remove Judicial Review.

-

Convert democracy into authoritarian rule.

-

Take away citizens’ core Fundamental Rights.

Significance of the Debate

-

Preserves Democratic Balance: Neither Parliament nor Judiciary can become supreme.

-

Ensures Flexibility with Stability: The Constitution can evolve but not collapse.

-

Protects Citizens’ Rights: Guarantees that no government can take away basic freedoms.

-

Prevents Constitutional Dictatorship: The Basic Structure acts as a permanent safeguard.

Current Perspective

-

Parliament continues to amend the Constitution for governance reforms, social justice, and economic development.

-

Judiciary ensures amendments don’t dilute democracy or citizens’ rights.

-

Together, they maintain Constitutional equilibrium — the hallmark of Indian democracy.

FAQs

Q1. Can Parliament amend Fundamental Rights?

Yes, but not in a way that damages the Basic Structure of the Constitution.

Q2. What is the Basic Structure Doctrine?

A judicial principle ensuring that core features like democracy, secularism, and judicial review cannot be amended.

Q3. Can the Supreme Court strike down a Constitutional Amendment?

Yes — if it violates the Basic Structure (e.g., Minerva Mills, I.R. Coelho).

Q4. Which Article provides for Constitutional Amendments?

Article 368 empowers Parliament to amend the Constitution.

Q5. Which Fundamental Right was removed?

The Right to Property (Article 31) — converted into a legal right via the 44th Amendment (1978).

Conclusion

-

Parliament can alter Fundamental Rights, but within constitutional limits.

-

The Basic Structure Doctrine ensures that India remains a democracy governed by rule of law, not by the whims of the majority.

-

This ongoing “conversation” between Parliament and Judiciary sustains India’s living Constitution — flexible yet firm.

India’s strength lies not in one branch dominating another but in their dynamic balance that protects every citizen’s right to freedom, equality, and justice.

Avinash Jaiswal is the Founder of Vidya Planet, is dedicated to improving the quality of learning through structured, clear, and authentic educational content. His work reflects a consistent effort to simplify academic concepts and present them in a way that supports meaningful understanding.