Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction:

The Indian Constitution is far more than a static legal document; it is a covenant between the state and its people, a dynamic blueprint for a just society born from the ashes of colonial subjugation. Its preamble, a solemn resolution, promises to secure for all citizens Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. But these lofty ideals would remain mere poetic aspirations without a robust mechanism for their enforcement. This mechanism is enshrined in Part III of the Constitution, a sacrosanct charter of Fundamental Rights.

These rights are the bedrock upon which the edifice of Indian democracy stands. They represent a conscious inversion of the colonial paradigm, where the individual was subject to the arbitrary will of the state. The Fundamental Rights place the individual at the centre, arming them with legal guarantees against the potential tyranny of majority rule and state power. This article embarks on a detailed exploration of these rights—their philosophical origins, their intricate classification, their transformative journey through judicial interpretation, their limitations, and the powerful mechanisms that breathe life into them. To understand Fundamental Rights is to understand the very soul of the Indian Republic.

Part 1: The Historical and Philosophical Foundations

The genesis of Fundamental Rights in India cannot be divorced from its historical context. Centuries of foreign rule, and particularly the oppressive laws enacted under the British Raj, had made Indians acutely aware of the perils of unfettered state power. Laws like the Rowlatt Act of 1919, which allowed detention without trial, were stark reminders of a system where individual liberties were expendable.

The freedom struggle was, in essence, a struggle for these very rights. The Motilal Nehru Report of 1928 was one of the first official documents to demand a constitutional guarantee of rights for the people of India. The experiences of the Holocaust and World War II further galvanized the global community towards codifying human rights, an impulse that resonated deeply with the framers of the Indian Constitution.

The Constituent Assembly, a body of unparalleled erudition and vision, undertook the monumental task of drafting this charter. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the chairman of the Drafting Committee, and his colleagues did not create these rights in a vacuum. They were keen students of constitutional law worldwide. The inspiration was eclectic:

The American Constitution: The concept of a Bill of Rights and the power of judicial review were significant influences.

The Irish Constitution (Bunreacht na hÉireann): Provided clues on the Directive Principles of State Policy and the language of certain rights.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR): Adopted by the UN in 1948, its principles overlapped with the Assembly’s deliberations, reinforcing the universality of the rights they were enshrining.

However, the Indian approach was distinct. It was not a mere imitation. The framers tailored these rights to address India’s unique social maladies—deep-seated caste discrimination, religious pluralism, and widespread poverty. This is why the Right to Equality boldly includes the abolition of untouchability, and the Right against Exploitation explicitly prohibits forced labour. The philosophy was clear: these rights were not just about negative liberty (freedom from the state), but also about creating positive conditions for a transformative social democracy.

Part 2: A Detailed Examination of the Six Categories of Fundamental Rights

Part III of the Constitution, from Articles 12 to 35, meticulously details these rights. For a structured understanding, they are best analysed under their six classic categories.

1. The Right to Equality (Articles 14-18)

This is the first and perhaps the most significant group of rights, designed to dismantle hierarchical structures and establish a level playing field.

Article 14: Equality before Law and Equal Protection of Laws: This is the cornerstone. “Equality before the law” is a negative concept, implying the absence of any special privilege for any individual. The monarch, the commoner, and the state are all subject to the same law. “Equal protection of the laws,” a phrase borrowed from the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, is a more positive concept. It requires the state to treat all persons in similar circumstances alike. It does not mean that all laws must be universal. The state can classify persons for legislative purposes, but this classification must be based on an intelligible differential and have a rational nexus with the objective the law seeks to achieve. This is known as the “Doctrine of Reasonable Classification,” which prevents arbitrary state action.

Article 15: Prohibition of Discrimination: This article explicitly prohibits the state from discriminating against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. It applies to access to shops, public restaurants, hotels, places of public entertainment, and the use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, and roads maintained by state funds. Crucially, this article has been the basis for progressive legislation and judicial rulings, allowing for “protective discrimination” or reservations for women, children, and socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs).

Article 16: Equality of Opportunity in Public Employment: This guarantees equal opportunity for all citizens in matters relating to employment or appointment to any public office. Like Article 15, it permits reservations for backward classes if they are not adequately represented in the state services. It also allows the state to prescribe residence requirements for certain posts.

Article 17: Abolition of Untouchability: This is a revolutionary provision. It doesn’t just prohibit untouchability; it “abolishes” it and makes its practice in any form a punishable offence. The Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955 (renamed the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1976) was enacted to enforce this article, representing a direct constitutional assault on a deep-rooted social evil.

Article 18: Abolition of Titles: This article prohibits the state from conferring any titles (like “Sir,” “Rai Bahadur”) except for military or academic distinctions. It also prohibits Indian citizens from accepting titles from any foreign state. The awards like Bharat Ratna, Padma Vibhushan, etc., are not considered titles under this article but are merely decorations or awards.

2. The Right to Freedom (Articles 19-22)

This group guarantees the essential liberties required for an individual’s personal and intellectual development.

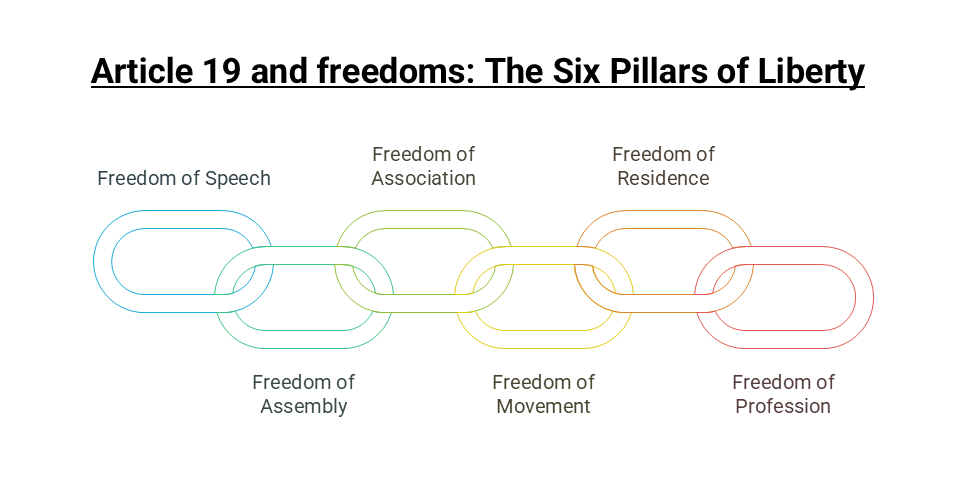

Article 19: Protection of Six Freedoms: This article grants all citizens six specific freedoms. However, recognizing that no freedom can be absolute in a complex society, it couples each freedom with “reasonable restrictions” that can be imposed by law on specified grounds like public order, sovereignty, and morality.

Freedom of Speech and Expression: This includes the freedom to express one’s opinions freely, through speech, writing, printing, or any other medium. The Supreme Court has held that this freedom includes the freedom of the press, the right to information, and the right to silence.

Freedom to Assemble Peaceably and Without Arms: This allows citizens to hold public meetings and processions. Restrictions can be imposed in the interest of public order.

Freedom to Form Associations or Unions: This enables citizens to form associations, unions, co-operative societies, and even political parties.

Freedom to Move Freely Throughout the Territory of India: This ensures the right of locomotion without barriers within the country.

Freedom to Reside and Settle in Any Part of India: This allows citizens to choose their place of residence, promoting national integration.

Freedom to Practice Any Profession, or to Carry on Any Occupation, Trade or Business: This guarantees the right to choose one’s livelihood, though the state can prescribe professional or technical qualifications for carrying on any trade.

Article 20: Protection in Respect of Conviction for Offences: This provides three crucial safeguards to an accused person:

No Ex-Post-Facto Law: A person cannot be convicted for an act that was not an offence at the time of its commission.

No Double Jeopardy: No person can be prosecuted and punished for the same offence more than once.

No Self-Incrimination: No person accused of an offence can be compelled to be a witness against themselves.

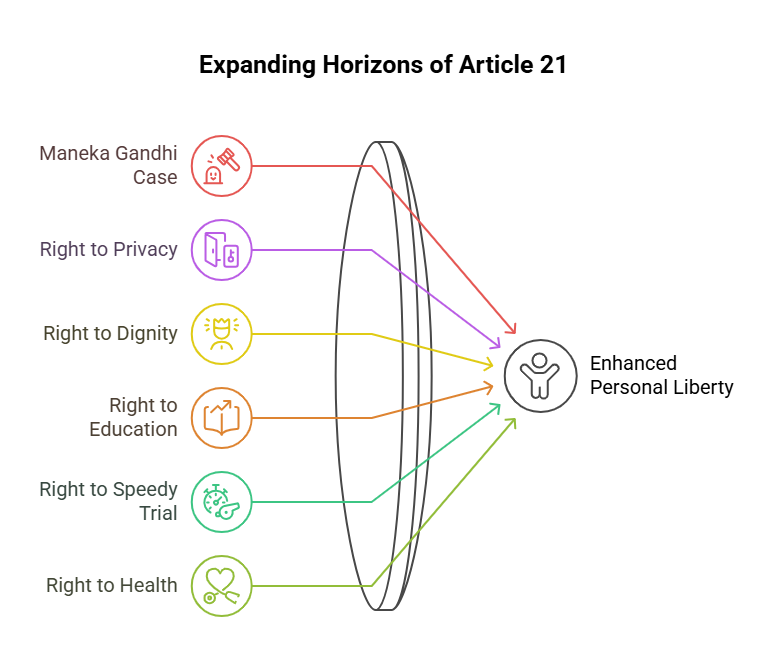

Article 21: Protection of Life and Personal Liberty: This is the most celebrated and dynamically interpreted provision. It simply states, “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” Initially interpreted narrowly, the Supreme Court, in the landmark case of Maneka Gandhi vs. Union of India (1978), revolutionized this article. The Court held that the “procedure established by law” must be “fair, just, and reasonable,” not just any procedure. This opened the floodgates for judicial activism. Through this article, the Supreme Court has read into it a plethora of unenumerated rights, including:

Right to Privacy

Right to Dignity

Right to Education (until it was made a separate fundamental right under Article 21A)

Right to Speedy Trial

Right to Free Legal Aid

Right against Torture

Right to a Clean Environment

Right to Health

Right to Livelihood

Article 22: Protection Against Arrest and Detention: This article lays down procedural safeguards for individuals who are arrested or detained. It includes the right to be informed of the grounds of arrest, the right to consult a lawyer, and the right to be produced before a magistrate within 24 hours. It also distinguishes between punitive detention (after a crime) and preventive detention (to prevent a crime), laying down specific, though less rigorous, procedures for the latter.

3. The Right against Exploitation (Articles 23-24)

This category targets socially sanctioned forms of exploitation.

Article 23: Prohibition of Traffic in Human Beings and Forced Labour: It prohibits human trafficking, begar (forced labour without payment), and other similar forms of forced labour. Any contravention of this provision is a punishable offence.

Article 24: Prohibition of Employment of Children in Factories, etc.: It prohibits the employment of children below the age of 14 years in any factory, mine, or other hazardous employment. This has been bolstered by legislation like the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act.

4. The Right to Freedom of Religion (Articles 25-28)

In a deeply religious and pluralistic country like India, this right is crucial for maintaining public order and harmony.

Article 25: Freedom of Conscience and Free Profession, Practice, and Propagation of Religion: This guarantees to every person the freedom of conscience and the right to profess, practice, and propagate religion. However, this freedom is subject to public order, morality, and health. The state is also empowered to regulate or restrict any economic, financial, political, or other secular activity associated with religious practice and to throw open Hindu religious institutions of a public character to all classes of Hindus.

Articles 26-28: These articles grant religious denominations the right to manage their own affairs, establish religious institutions, and own property. They also ensure that no religious instruction is provided in educational institutions wholly maintained by state funds.

5. Cultural and Educational Rights (Articles 29-30)

These rights are designed to protect the interests of minority communities and preserve the country’s diverse cultural heritage.

Article 29: Protection of Interests of Minorities: Any section of citizens residing in India having a distinct language, script, or culture has the right to conserve the same. It also prohibits discrimination in admission to state-funded educational institutions on the grounds of religion, race, caste, or language.

Article 30: Right of Minorities to Establish and Administer Educational Institutions: This grants all religious and linguistic minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. The state cannot discriminate against these institutions in granting aid.

6. The Right to Constitutional Remedies (Article 32)

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar famously hailed this article as the “very soul of the constitution and the very heart of it.” Without an enforcement mechanism, the preceding rights would be meaningless. Article 32 grants citizens the right to move the Supreme Court directly for the enforcement of their Fundamental Rights. The Supreme Court is empowered to issue directions, orders, or writs for this purpose. These writs, with their origins in English common law, are powerful tools:

Habeas Corpus: “To have the body.” A command to produce a detained person before the court to examine the legality of their detention.

Mandamus: “We command.” A command issued to a public official or body to perform a public duty they are obliged to do.

Prohibition: Issued by a higher court to a lower court or tribunal to prevent it from exceeding its jurisdiction.

Certiorari: To quash the order of a lower court or tribunal passed without jurisdiction or in violation of natural justice.

Quo Warranto: “By what authority?” It is used to challenge a person’s right to hold a public office.

This right is itself a Fundamental Right, making the Supreme Court the ultimate guardian of the people’s liberties.

Part 3: The Dynamic Role of the Judiciary: From Interpreter to Activist

The story of Fundamental Rights is incomplete without acknowledging the role of the Indian judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court. The Court has transformed from a passive interpreter to an active guardian and even a catalyst for social change.

The Era of Procedure: A.K. Gopalan vs. State of Madras (1950): Initially, the Court took a restrictive view. In the Gopalan case, it held that Article 21 only required a validly enacted law, and the court would not examine the “fairness” of the procedure. This meant that if Parliament passed a law allowing detention, the court would not question it.

The Paradigm Shift: Maneka Gandhi vs. Union of India (1978): This case marked a tectonic shift. The Court overruled the narrow interpretation of Gopalan and declared that the procedure under Article 21 must be “right, just, and fair,” and not arbitrary or oppressive. It also established the doctrine of “inter-relationship of rights,” stating that the freedoms under Article 19 give meaning to the “personal liberty” under Article 21. This opened the door for an expansive reading of the Constitution.

Public Interest Litigation (PIL): The most significant innovation of the Indian judiciary. The Supreme Court relaxed the traditional rule of locus standi (the right to bring a case), allowing any public-spirited individual or organization to file a petition on behalf of the poor, illiterate, or oppressed who could not access the courts. Through PILs, the Court has addressed issues ranging from environmental degradation and prisoner rights to bonded labour and police brutality, making Fundamental Rights a tangible reality for millions.

The Expansion of Article 21: Post-Maneka Gandhi, the Supreme Court has engaged in judicial law-making, reading a host of new rights into the umbrella of “life and personal liberty.” Cases like Vishaka vs. State of Rajasthan (guidelines against sexual harassment) and Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) vs. Union of India (right to privacy as a fundamental right) are testaments to this activist role.

Part 4: Limitations and the Balance with State Interest

While powerful, Fundamental Rights are not absolute. The Constitution itself provides for their curtailment under specific circumstances.

Reasonable Restrictions: The freedoms under Article 19 are explicitly subject to reasonable restrictions in the interests of sovereignty, public order, decency, etc.

Directive Principles of State Policy: Part IV of the Constitution contains Directive Principles which are fundamental in the governance of the country but are not enforceable in court. The judiciary has often tried to achieve a “harmonious construction” between the justiciable Fundamental Rights and the non-justiciable Directive Principles, allowing the state to implement welfare legislation that may incidentally restrict certain rights.

Power of Amendment (Article 368): Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution, including the chapter on Fundamental Rights. However, after the landmark case of Kesavananda Bharati vs. State of Kerala (1973), the Supreme Court asserted that Parliament cannot alter the “basic structure” of the Constitution. The Fundamental Rights are considered an integral part of this basic structure, meaning while they can be amended, their core essence cannot be destroyed.

Emergency Provisions (Article 352): During a proclamation of a National Emergency, the enforcement of Fundamental Rights under Article 19 can be suspended. Furthermore, the President can suspend the right to move any court for the enforcement of other rights (except Articles 20 and 21).

Conclusion: A Living, Breathing Charter

Seventy-five years after its adoption, the chapter on Fundamental Rights remains a living, breathing charter. It is not frozen in the amber of 1950. It has evolved through legislative action and, most profoundly, through judicial interpretation, to meet the challenges of a changing society—from the industrial age to the digital era. It has been the legal weapon to fight social injustice, the shield against state excesses, and the moral compass guiding the nation towards its constitutional goals.