Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

The population of a state is divided into two classes: citizens and aliens. A citizen of a state is a person who enjoys full civil and political rights. He enjoys full membership of the political community or state. Citizens are different from aliens or mere residents who do not enjoy all these rights. In India, aliens do not enjoy all the fundamental rights secured to the citizens. Citizenship carries with it certain advantages conferred by the constitution. Aliens do not enjoy this advantages.

Constitutional provisions:

The constitution does not lay down a permanent or comprehensive provision relating to citizenship in India. Part II of the constitution simply describes classes of persons who would be deemed to be the citizens of India at the commencement of the constitution, the 26th January 1950, and leave the entire Law of citizenship to be regulated by law made by Parliament. Article 11 expressly confers power on parliament to make laws to provide for such matters. In exercise of its power the parliament has enacted the Indian citizenship act, 1955. This act provides for the acquisition and termination of citizenship subsequently to the commencement of the constitution.

Citizenship at the commencement of the constitution i.e., January 26, 1950- the following persons under articles 5 to 8 of the constitution of India shall become citizens of India at the commencement of the constitution:

- Citizenship by Domicile

- Citizenship of emigrants from Pakistan

- Citizenship of migrants to Pakistan

- Citizenship of Indians abroad

Article 5: Citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution.

At the commencement of this Constitution, every person who has his domicile in the territory of India and

(a) who was born in the territory of India; or

(b) either of whose parents was born in the territory of India; or

(c) who has been ordinarily resident in the territory of India for not less than five years immediately preceding such commencement, shall be a citizen of India.

Citizenship by Domicile (Article 5)- to be entitled to citizenship by domicile, Article 5 lays down two conditions. First, at the commencement of the constitution, a person must have his domicile in the territory of India. Second, such a person must fulfil any of the three conditions mentioned in the article.

Domicile in India is an essential requirement for acquiring Indian citizenship. The term “domicile” is not defined in the constitution. Ordinarily, it means a permanent home or place where a person resides with the intention of remaining there for an indefinite period. Domicile is not the same thing as residence. Domicile is not only residence; it is residence coupled with intention to live indefinitely in a place.

Article 6: Rights of citizenship of certain persons who have migrated to India from Pakistan.

Notwithstanding anything in article 5, a person who has migrated to the territory of India from the territory now included in Pakistan shall be deemed to be a citizen of India at the commencement of this Constitution if—

(a) he or either of his parents or any of his grandparents was born in India as defined in the Government of India Act, 1935 (as originally enacted); and

(b) (i) in the case where such person has so migrated before the nineteenth day of July, 1948, he has been ordinarily resident in the territory of India since the date of his migration, or

(ii) in the case where such person has so migrated on or after the nineteenth day of July, 1948, he has been registered as a citizen of India by an officer appointed in that behalf by the Government of the Dominion of India on an application made by him therefor to such officer before the commencement of this Constitution in the form and manner prescribed by that Government:

Provided that no person shall be so registered unless he has been resident in the territory of India for at least six months immediately preceding the date of his application.

This article deals with persons who have migrated from Pakistan to India before the commencement of the constitution. Such persons have, for the purpose of citizenship, been classified into two categories, namely, 1) those who came to India before 19th July 1948, and 2) those who came on or after 19th July 1948. Further specific conditions are mentions under both these categories.

Article 7: Rights of citizenship of certain migrants to Pakistan.

Notwithstanding anything in articles 5 and 6, a person who has after the first day of March, 1947, migrated from the territory of India to the territory now included in Pakistan shall not be deemed to be a citizen of India:

Provided that nothing in this article shall apply to a person who, after having so migrated to the territory now included in Pakistan, has returned to the territory of India under a permit for resettlement or permanent return issued by or under the authority of any law and every such person shall for the purposes of clause (b) of article 6 be deemed to have migrated to the territory of India after the nineteenth day of July, 1948.

This article deals with the migration of population from India to Pakistan and lays down special criteria for deciding who shall not be deemed to be such citizens. Article 7 overrides article 5, for even if a person is a citizen of India by virtue of article 5, he cannot deem to be a citizen of India, if he has migrated to Pakistan after 1 march 1948. An exception is made……

Article 8: Rights of citizenship of certain persons of Indian origin residing outside India.

Notwithstanding anything in article 5, any person who or either of whose parents or any of whose grandparents was born in India as defined in the Government of India Act, 1935 (as originally enacted), and who is ordinarily residing in any country outside India as so defined shall be deemed to be a citizen of India if he has been registered as a citizen of India by the diplomatic or consular representative of India in the country where he is for the time being residing on an application made by him therefor to such diplomatic or consular representative, whether before or after the commencement of this Constitution, in the form and manner prescribed by the Government of the Dominion of India or the Government of India.

This article deals with persons who or whose parents or grandparents were born in India, but are residing abroad. Such persons shall be deemed to be citizens of India by the diplomatic or consular representative of India in the country where they are residing. The registration shall be made only on the application from the citizen.

Article 9: Persons voluntarily acquiring citizenship of a foreign State not to be citizens.

No person shall be a citizen of India by virtue of article 5, or be deemed to be a citizen of India by virtue of article 6 or article 8, if he has voluntarily acquired the citizenship of any foreign State

This article enacts that a person who has voluntarily acquired the citizenship of a foreign state shall not remain a citizen of India. It deals only with voluntarily acquisition of citizenship of a foreign state before the constitution came into force.

Article 10: Continuance of the rights of citizenship.

Every person who is or is deemed to be a citizen of India under any of the foregoing provisions of this Part shall, subject to the provisions of any law that may be made by Parliament, continue to be such citizen.

Article 11: Parliament to regulate the right of citizenship by law

Nothing in the foregoing provisions of this Part shall derogate from the power of Parliament to make any provision with respect to the acquisition and termination of citizenship and all other matters relating to citizenship.

Citizenship Under the Citizenship Act, 1955

ACQUISITION OF CITIZENSHIP

Citizenship by birth (section 3): Any person born in India on or after Jan 26,1950 is a citizen of India provided his/her father is not an enemy alien or representative of a diplomatic mission.

Citizenship by Descent (section 4): A person born outside India on or after Jan 26, 1950 shall be a citizen of India by descent if his father or mother isa citizen of India at the time of his birth; provided such birth is registered in any of Indian consulates.

Citizenship by Registration (section 5): A person can acquire citizenship by registering themselves with prescribed authority. Such categories of persons are-

- Persons of Indian origin residing outside the territories of India

- Those persons of Indian origin who are ordinarily residents in India and have been so resident for 6 months immediately before making application for registration

- Women who are married to citizens of India

- Children of Indian citizens

- Adult citizens of Indian commonwealth country or republic of Ireland

Citizenship by Naturalization (section 6): A foreign citizen not covered by any of the above methods can get Indian citizenship on application of naturalization to the Government of India

Citizenship by Acquisition of a New Territory (section 7): If a new territory becomes a part of India, the government of India specifies the persons of that territory who shall be citizens of India.

How a person can lose Nationality?

The Citizenship Act envisages three situations under which a citizen of India may loose his nationality.

By Renunciation (section 9): If any citizen of India who is also a national of another country renounces his citizenship through declaration of in prescribed manner, he ceases to be an Indian citizen.

By Termination (section 10): By operation of law when one acquires citizenship of another country.

Deprivation (section 11): Section 10 of the Citizenship act 1955 empowers the government to deprive a citizen of his citizenship by issuing an order. However, this power may not be issued in case of every citizen. It applies only to those, who acquired Indian citizenship. This might be because of obtaining citizenship on false documentations etc.

Judicial Oversight

Indian courts have repeatedly interpreted the constitutional provisions and the Act. Notable decisions include:

- K. Sinha v. Union of India (1978) – clarified the meaning of “domicile” under Article 5.

- Shyam Singh v. Union of India (2015) – emphasized procedural fairness in deprivation of citizenship.

- R. Batra v. Union of India (2020) – upheld the government’s power to amend the Act but warned against arbitrary denial of citizenship.

These judgments ensure that administrative actions under the Act remain subject to constitutional safeguards.

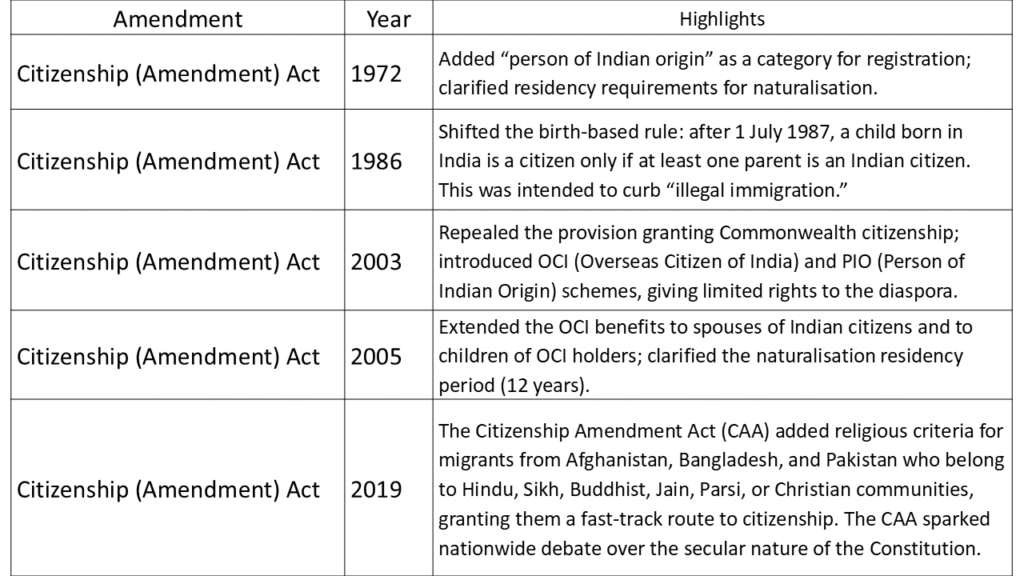

Major amendments

Dual Citizenship

The constitution of India does not allow dual citizenship, i.e., holding Indian citizenship and citizenship of a foreign country simultaneously. The Government of Indian decided to grant Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) which most people mistakenly refer as ‘dual citizenship’. Persons of Indian origin (PIOs) of certain category who migrated from India and acquired citizenship of a foreign country other than Pakistan and Bangladesh, are eligible for grant of OCI as long as their home countries allow dual citizenship in some form or the other under their local laws.

OCI is not the same as being a regular Indian Citizen:

- No Indian Passport

- No voting rights

- Cannot be candidate for Lok Sabha / Rajya Sabha / Legislative Assembly/ Council

- Cannot hold constitutional post such as President, Vice President, Judge of Supreme Court / High Court etc

- Cannot normally hold employment in the government

But the person will be entitled to benefits such as:

- Multiple entry, multipurpose lifelong visa to visit India;

- Exemption from reporting to police authorities for any length of stay in India;

- Parity with NRIs in financial, economic, and educational fields except in the acquisition of agriculture or plantation properties

Conclusion

The Indian Constitution, through Articles 5-11, establishes a foundational, inclusive, yet singular concept of citizenship—one that unites every Indian to the Union regardless of state boundaries. The Citizenship Act of 1955, along with its subsequent amendments, translates these constitutional ideals into specific regulations that govern who is eligible for citizenship, the circumstances under which citizenship may be revoked, and the rights and responsibilities that accompany it. While the fundamental principle of single citizenship remains unchanged, the law has adapted to address the realities of a vast diaspora, migrations following Partition, and current security issues.

For the average citizen, the essential takeaway is straightforward: citizenship grants full political and civil rights, but it also requires loyalty and adherence to the law. For those seeking citizenship, the Act provides clear avenues—birth, descent, registration, or naturalization—each with its distinct set of criteria. As India continues to develop and engage with the global community, the equilibrium between inclusivity and national integrity will keep the conversation on citizenship dynamic, and the Constitution along with the Citizenship Act will continue to serve as the dual foundations guiding that journey.

FAQs

Q.1 Can a child born abroad to Indian parents automatically become a citizen?

Yes, if at least one parent is an Indian citizen at the time of birth and the birth is registered at an Indian consulate (Section 4).

Q.2 Is it possible to regain Indian citizenship after renouncing it?

Yes, by applying for naturalisation or registration, subject to the same conditions as any other foreign national.

Q.3 Do OCI holders have voting rights?

No. OCI confers many economic and travel benefits but does not grant political rights.

Q.4 What happens if a citizen acquires foreign citizenship inadvertently (e.g., by marriage)?

The acquisition is considered “voluntary” under Article 9; the government may terminate Indian citizenship unless the person obtains a renunciation certificate for the foreign citizenship.

Q.5 Can a person be a citizen of both India and Pakistan?

No. Dual citizenship is prohibited; however, a person may hold dual nationality if one of the countries permits it, but India will still treat the individual as a non‑citizen for Indian law purposes.

Jyoti Bhojwani is a highly motivated first-year LLB student at Banaras Hindu University with a strong passion for clear and accurate legal communication. Leveraging prior experience in proofreading and content creation, Jyoti is committed to delivering well-researched and accessible legal analysis. She is dedicated to developing expertise in legal writing and contributing valuable content to the legal community.