Overview

Property disputes have increased significantly in Joint Hindu families in recent years. Equal property allocation among family members is required by the circumstances. Only male family members were deemed entitled to inherit the properties and were referred to as coparceners, according to the history of Hindu personal laws. The coparcenary property is regarded as jointly owned, and only a coparcener has the authority to request a partition of the property.

As the previous system violated the essential rights of the Right to Equality established in the Indian constitution, people began to realize that the head of the household should think about making women coparceners in their property. As a result, the Hindu Succession Act of 1955 needed to be amended.

Coparcenary

Coparcenary refers to an individual who possesses a birthright to their joint family property. It is a narrow body of persons within a joint family, and consists of the father’s son, son’s son, son’s son’s son and in its continuance, the existence of a father- son relationship is not mandatory. The conception of a coparcenary is that a common male ancestor with his lineal descendants in the male line with four degrees counting from such ancestor ( i.e., three degrees exclusive of such ancestor). No coparcenary can commence without a common male ancestor, though after his death it may consist of collaterals, such as brothers, uncles, cousins nephews, etc. A coparcenary is purely a creature of law and cannot be created by contract.

No female can be a coparcener under the Mitakshra Law, though she may have the right to maintenance in some cases even to succession.

Ordinarily, a coparcenary will end with the death of the sole surviving coparcener but if he dies leaving a widow having authority to adopt a son to him, coparcenary will be continued. The reason is that a family cannot be ended if there is a possibility of adding any male member to it.

HISTORY

The origins of Hindu personal laws can be traced back to the period between 1100 and 1200 A.D. There exist two primary schools of Hindu law, namely the ‘Mitakshara School of Law’ and the ‘Dayabhaga School of Law.’ The Mitakshara School of Law emphasizes the principle of survivorship. Male members of the family, upon birth, acquire an equal interest in all ancestral property held by their father. Following the father’s demise, the son, as the survivor, assumes possession of the property. Under this school of Hindu law, only agnates, which refers to male family members, possess rights over ancestral properties. Daughters and women are excluded from rights to such joint family properties.

The Dayabhaga School of Hindu Law adheres to the Sapinda concept, which pertains to individuals who can offer Pinda (a ritual offering to deceased family elders). In this school, cognates, encompassing both males and females, are permitted to make such offerings. The succession rules established in this school allow both sons and daughters to inherit the family’s joint property, thereby designating them as coparceners.

Over time, however, women began to advocate for their right to inherit their father’s properties. In situations where a daughter is the sole child of her parents, questions arise regarding her entitlement to the property.

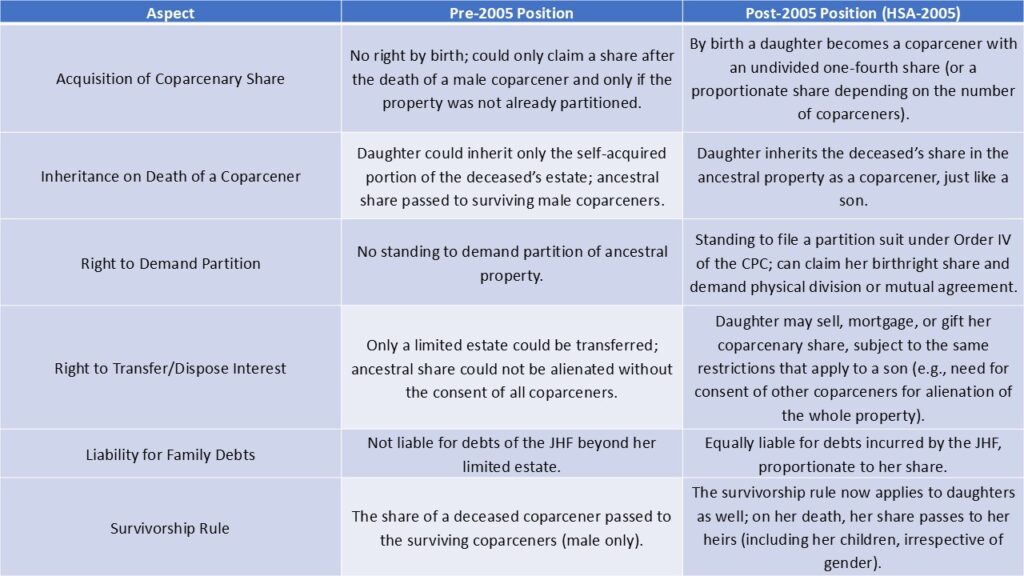

Daughters had very few rights with regard to coparcenary property prior to the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005. Daughters did not have the right to request a partition while the coparceners were still alive, even if they could inherit a portion of their father’s fortune upon his passing. Due to this legal exclusion, daughters were unable to assert their claims to property, which remained firmly in the hands of male relatives, despite being members of the family. female agency and financial stability were restricted because female rights were dependent on the behaviour of male members.

Key Provisions of the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005

Wide sweeping changes have been introduced in the composition of the joint family by way of Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005. By virtue of this Amendment Act, now the daughter of a coparcener is also a coparcener in her own right and in the same manner as a son. Section 6, which outlines the rights of coparceners in Hindu Undivided Families (HUFs), is a crucial modification brought about by the amendment. Prior to the amendment, daughters were limited to mere membership and could not assert equal rights in ancestral property because the concept of coparcenary was solely male. However, by giving girls the same coparcenary rights as sons, the 2005 Amendment fundamentally changed this structure. A daughter now has the legal right to inherit property from her father’s ancestry since she is recognised as a coparcener by birth in the same way as a son under the amended Section 6(1).

Furthermore, Section 6(3) highlights that the share of a deceased coparcener’s interest in the property will be distributed equally among both sons and daughters, thereby reinforcing their status as equal stakeholders within the HUF. The ramifications of this amendment for women’s property rights are significant. By acknowledging daughters as coparceners, the amendment empowers them to proactively claim a portion of ancestral property instead of relying on male relatives to transfer their interests. This legal acknowledgment not only improves women’s financial security but also grants them the authority to manage and control property, thus promoting greater economic independence. Moreover, daughters are now eligible to serve as the Karta (manager) of the HUF if they are the senior-most coparcener, which enables them to assume leadership positions within the family structure. Additionally, the amendment has established the right for daughters to request partition, allowing them to assert their claims to ancestral property without the constraints of traditional patriarchal norms. This newfound capacity to seek partition guarantees that daughters can actively exercise their rights and protect their interests, challenging the historically entrenched gender biases that have restricted women’s access to property. In summary, the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005, has fundamentally transformed the legal framework for daughters in Hindu law, placing them on equal footing with sons regarding coparcenary rights and property ownership.

Landmark Judgements

Since the passage of the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005, numerous important judicial decisions have influenced the understanding and execution of daughters’ rights as coparceners. These judgments have been instrumental in elucidating the retroactive enforcement of the amendment, thereby strengthening the principles of gender equality and justice in property rights.

One notable case is Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma (2020), in which the Supreme Court of India clearly affirmed that daughters have coparcenary rights in their father’s property from birth, irrespective of whether they were born before or after the 2005 amendment. This case emerged from a familial dispute regarding property rights following the death of a father. The court determined that the provisions of the amended Section 6 are applicable retroactively, thereby empowering daughters with equal rights to assert their claim to a share in the ancestral property, even if their father had died prior to the amendment’s enactment. This ruling underscored that the right to coparcenary is intrinsic and is not contingent upon the father’s survival or the timing of the amendment.

Another significant case is Danamma v. Amar Singh (2018), where the Supreme Court reaffirmed that daughters’ rights to coparcenary property are not dependent on their father’s status at the time of the amendment. The court reiterated that daughters possess the same rights as sons in coparcenary property, thereby removing any uncertainty regarding their entitlement. This ruling emphasized the necessity for legal acknowledgment of daughters’ rights in ongoing disputes and confirmed that daughters should be regarded as coparceners, regardless of their birth date.

In addition to these landmark cases, other judicial interpretations have further reinforced the retroactive application of the amendment. These judicial rulings collectively highlight the significant influence of the 2005 amendment in advancing gender equality within Hindu inheritance law. By confirming that daughters possess coparcenary rights equivalent to those of sons, these decisions not only rectify historical wrongs but also facilitate a more just distribution of property rights among Hindu families. Such rulings exemplify a wider commitment to upholding constitutional values of equality and justice, showcasing the judiciary’s role in confronting patriarchal traditions entrenched in customary practices.

Conclusion

The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005 marks a pivotal moment in Indian property law. By bestowing daughters with the status of coparceners from birth, the amendment eliminated a long-standing gender bias, aligning statutory law with the constitutional promise of equality. While the amendment has largely succeeded in promoting gender equality, challenges persist—especially regarding retroactive claims and alignment with other personal laws. Ongoing judicial oversight and potential legislative adjustments will be crucial to ensure that the essence of the amendment—equality, fairness, and social justice—is fully realized in practice.