Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

The Indian Contract Act of 1872 was passed on April 25, 1872, and went into effect on September 1st, 1872. It includes the contractual rights that Indian citizens have been awarded. It gives the contracting parties rights, responsibilities, and duties that enable them to properly complete business transactions, ranging from routine transactions to demonstrating the operations of multinational corporations.

In common talks in India, the phrases “agreement” and “contract” are frequently used interchangeably, which could cause confusion in legal circumstances where exact language is important. Legally speaking, they reflect different notions, particularly when differentiating between an agreement and a contract, despite their colloquial similarities. A contract is a subset of agreements that satisfy certain legal requirements and are legally enforceable, whereas an agreement generally refers to any mutual understanding or arrangement between parties, regardless of enforceability. Since agreements and contracts govern a variety of activities and interactions in Indian culture, it is essential to comprehend their subtleties. In order to establish legal relations for enforcement, contracts—as opposed to agreements—need particular legal components including offer, acceptance, consideration, and intention.

Statutory Definition

A legally enforceable agreement is referred to as a contract. An agreement is the most popular method of creating a contract. Mutual discussions may result in an agreement between the two parties. An agreement is created when one party makes an offer and the other accepts it; this agreement may be legally enforceable. Reciprocal pledges between the two parties make up an agreement. Each participant to a contract is legally obligated to keep his end of the bargain.

Section 2 (h) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 defines “contract” as “an agreement enforceable by law is a contract.”

Therefore, in order to create a contract, there must be: 1) an agreement; and 2) the agreement must be legally enforceable.

An agreement must meet all of the requirements listed in section 10 in order to be considered a contract. According to this section, an agreement is a contract when it is made for some consideration, between parties who are competent, with their free consent and a lawful object.

Section 2(e) defines an agreement as “every promise and every set of promises forming the consideration for each other.”

Both parties make promises in an agreement. Section 2 (b) says: “A proposal, when accepted, becomes a promise.” In other words, an agreement is a plan that has been accepted. Therefore, when one party makes a proposition and the other accepts it, a commitment is made. An agreement is a commitment made by the two parties to each other. A contract is an agreement, an agreement is a promise, and a promise is an accepted proposal. This is the essence of the definition process. Therefore, in the end, every agreement consists of a proposal from one party and its acceptance by the other.

Contract as civil obligation

The law of contract is limited to the enforcement of agreements made voluntarily. It does not encompass the entire scope of civil duties. There are various civil obligations, such as those required by legislation or created by norms, created by the acceptance of a trust, the breach of which may be subject to legal action under the law of torts or trusts, or under a statute, but they lie outside the area of agreement. The law of contract cannot cover everything completely. Numerous agreements stay beyond its scope because they fail to meet the conditions of an agreement. Moreover, there are a few agreements that fundamentally meet the conditions of a contract, like proposal, approval, contemplation, etc., yet fail to capture its essence and they are not enforced as it does not appear reasonable to do so therefore. They are excluded under the legal framework that the parties should not possess focused legal ramifications.

Essentials of a Valid Agreement and Valid Contract

Only those agreements which satisfy the essentials mentioned in section 10 become contracts.

Section 10: What agreements are contracts.—

All agreements are contracts if they are made by the free consent of parties competent to contract, for a lawful consideration and with a lawful object, and are not here by expressly declared to be void. Nothing herein contained shall affect any law in force in [India] and not hereby expressly repealed, by which any contract is required to be made in writing or in the presence of witnesses, or any law relating to the registration of documents.

All agreements are not enforceable by law, and, therefore all agreements are not contracts. Some agreements may be enforceable by law and others not. Thus, every contract is an agreement, but every agreement is not a contract. An agreement grows into a contract when the following conditions are satisfied:

- Offer And Acceptance:

An essential part of creating a contract is the offer and acceptance process. A legally enforceable contract may only be formed if one party makes an offer and the other party accepts it by making their own consent. Promises that constitute an agreement are made when the offer is accepted. It is possible to convey the acceptance explicitly or implicitly.

- Intention to create legal obligation:

There is no provision in the Indian Contract Act, 1872 requiring that an offer or its acceptance should be made with the intention of creating legal relations. But in English law it is a settled principle that to create a contract there must be a common intention of the parties to enter into legal obligations. A clue that intention to be legally bound is an essential requirement under the Indian Contract Act can be seen in the fact that a proposal has to be made with “willingness” to do business on the proposed terms. The use of the word “willingness” shows that intention to be bound by the proposal when accepted is an integral part of the concept of agreement.

- Consideration:

As per the section 25 of Indian Contract Act,1872 : “an agreement made without consideration is void, unless

(1) it is expressed in writing and registered under the law for the time being in force for the registration of 1[documents], and is made on account of natural love and affection between parties standing in a near relation to each other; or unless

(2) it is a promise to compensate, wholly or in part, a person who has already voluntarily done something for the promisor, or something which the promisor was legally compellable to do; or unless;

(3) it is a promise, made in writing and signed by the person to be charged therewith, or by his agent generally or specially authorized in that behalf, to pay wholly or in part a debt of which the creditor might have enforced payment but for the law for the limitation of suits.

In any of these cases, such an agreement is a contract.”

- Parties must be competent to Contract:

Who are competent to contract.—Every person is competent to contract who is of the age of majority according to the law to which he is subject, and who is of sound mind, and is not disqualified from contracting by any law to which he is subject.

- Free Consent

Consent is defined under sec 13 as: “Two or more persons are said to consent when they agree upon the same thing in the same sense.” Mere consent is not enough it has to be free consent. According to Sec 14: “Consent is said to be free when it is not caused by—

(1) coercion, as defined in section 15, or

(2) undue influence, as defined in section 16, or

(3) fraud, as defined in section 17, or

(4) misrepresentation, as defined in section 18, or

(5) mistake, subject to the provisions of sections 20, 21 and 22.

Consent is said to be so caused when it would not have been given but for the existence of such coercion, undue influence, fraud, misrepresentation or mistake.”

- Lawful Object and Lawful Consideration:

Section 23 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 tells what considerations and objects are lawful, and what are not. It declares that the consideration or object of an agreement is lawful, unless— it is forbidden by law ; or is of such a nature that if permitted, it would defeat the provisions of any law; or is fraudulent ; or involves or implies injury to the person or property of another; or the Court regards it as immoral, or opposed to public policy.

In each of these cases, the consideration or object of an agreement is said to be unlawful. Every agreement of which the object or consideration is unlawful is void.

- Must not be expressly void:

A contract must not be specifically declared void by the Indian Contracts Act or any other law in order to be deemed legal, as the Indian Contract Act, 1872, has established a specific set of contracts to be void. Wagering contracts are an example of a contract that has been specifically declared void.

- Contract must not be vague or uncertain:

A contract is deemed legitimate if its contents are interpreted as intended and are not ambiguous or imprecise. This is necessary to prevent future disagreements between the parties.

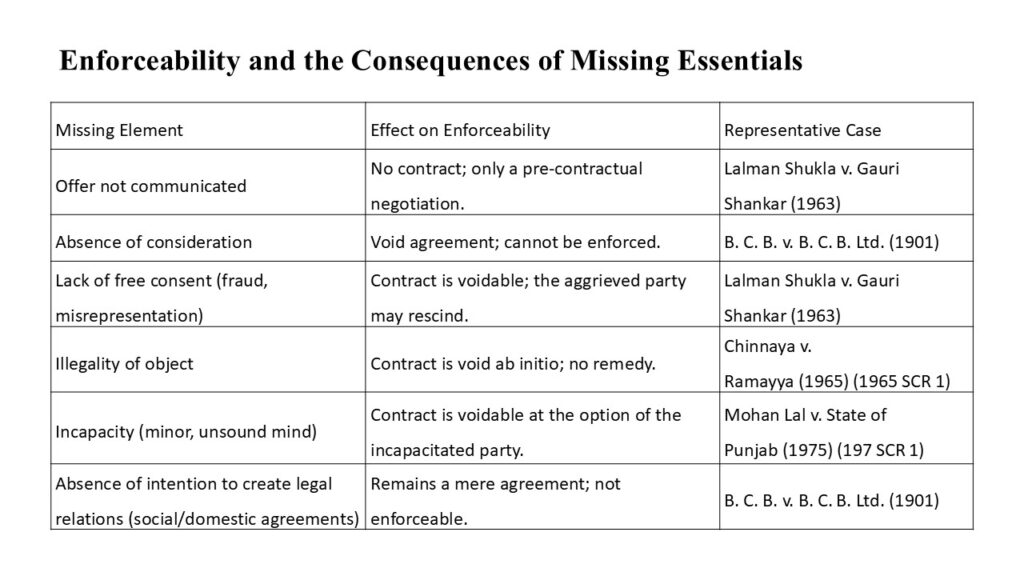

Illustrative Judicial Precedents

- Gauri Shankar v. Lalman Shukla (1963) AIR 124: The Supreme Court ruled that there was only a theoretical agreement and not a contract because the offer had not been communicated. The Court underlined that an offer and an acceptance need to be communicated and made simultaneously.

- C. B. v. B. C. B. Ltd. (1901): The Court determined that a share-subscription agreement was unenforceable due to the nonpayment of compensation, making it only an agreement. The document formed a contract as soon as the consideration was provided.

- M. K. Sinha v. Union of India (1987): The Court noted that a government procurement agreement that lacked a clear desire to establish legal relations remained an agreement and only became a contract upon the issuance of a formal award letter.

Conclusion

The distinction between an agreement and a contract is made explicit by the Indian Contract Act of 1872. An agreement only becomes a contract when it passes the statutory standard of enforceability outlined in Section 10, even though it marks the first convergence of wills. The case law—Lalman Shukla, B. C. B., R. M. K. Sinha, Chinnaya, and Mohan Lal—shows how judges carefully consider every crucial component before granting legal force.

A well-written agreement that foresees offer-acceptance dynamics, expresses consideration, affirms capacity, ensures free consent, and verifies lawful purpose will automatically become a contract. On the other hand, if any of these pillars are neglected, the parties may be left with a promise that is not enforceable, leaving them vulnerable to legal action and business damage.